It has been fashionable of late to talk of sport as a cure. Running, cycling, picking up clubs or racquets or bats, these are highly effective forms of therapy for many people – tackling a leaflet filling list of symptoms from high blood pressure, muscle tension, and obesity to more intangible complaints like low self-esteem, loneliness, and stress.

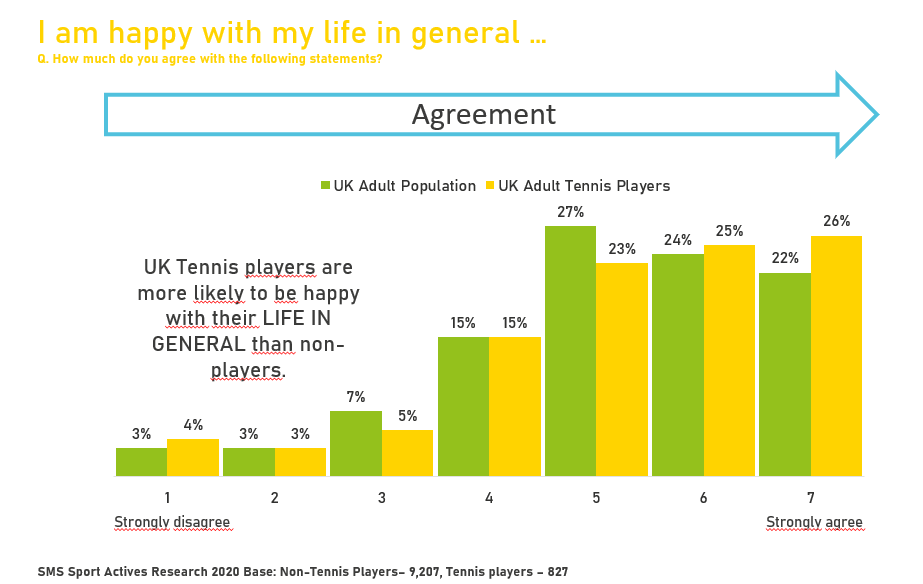

Traditionally when it comes to drawing lines between sport and health, we have tended to focus on this element of sport’s value – its role in treatment. This is the thinking, for example, that underlies social prescription, the practice of GPs encouraging patients to consider running, ebikes or golf among other types of exercise. A new report by UK Active has called for an expansion of the practice to help reduce pressure on the NHS. Yes, this is a clear string to sport’s bow, but there are many others. Less attention has been paid to the arguably more crucial question of whether sport can help prevent certain mental, physical and social ailments at source. After all, SMS participation research has, in the past, indicated that tennis players, for example, are slightly happier with their social life and life overall than the general population.

Yet, as we continue to live with Covid, and tempting as it is to promote sport’s role as a cure, we mustn’t fall into the trap of letting it be relegated to being only a cure. In fact, sport can be both cure, and, perhaps even more importantly, prevention.

One of the effects of the pandemic has been to make us all more aware of our personal wellbeing and the result is that many people are now seeking extra agency in how they spend their time, often leading to people saying no to social gatherings they might once have felt compelled to go to and yes to active habits that fit their lifestyle. If we can embed this, then 2022 might just be the year when society starts talking about how to instil sport earlier and more centrally in people’s lives. It might be the year when the discourse starts to shift from the value of working from home as a good way of being frugal with a household’s contact budget to working from home because it means more time for sport. It might be the year when civil servants having more time for peloton is not something we sneer at, but something we welcome. Even without a pandemic to promote home working, isn’t the chance to run 5k, play nine holes, ride a bike, or sneak in a set of tennis before or after work reason enough?

This chimes with what research is reiterating again and again. In golf, insights on behalf of the R&A have highlighted the mental, physical and social health value of a sport that is enhancing and even saving lives. It is one of the reasons SMS campaigned to keep golf (and other sports) open during lockdowns. More recently, our Sporting Journeys research highlighted how, among women, sport can have a series of transformative effects, whether helping women navigate menopause, bereavement, ageing and many other parts of life. It helped, the research showed, in a number of ways, fostering personal growth, social connections, escapism, and enjoyment. Under the surface too, plenty of testimony in that report hints at many women’s regret at stopping playing sport, at not taking it back up until it was needed as treatment. Sport cures, but it also prevents ailment. 2022 is the year we recognise that more actively.

In this, our evolving perception of sport’s social and health benefits is in keeping with our approach to treating the pandemic overall. Isolation, quarantine, vaccines – these are all preventative measures designed to stop people becoming ill or seriously ill rather than ways of treating illness once it develops. And, although treatment of COVID has come a long way in the short space of time since Spring 2020, including the recent development of the first oral antiviral drug, it is prevention as a means of breaking the chains of infection that remains our first and best defense against COVID. Sport can do the same – not for COVID itself, even if, by reducing obesity it can help prevent of COVID’s comorbidities – but for many of the other mental and physical challenges we all face in life. To do that will take time. It will take inclusive, welcoming messaging and affordable pricing that allows people to dip their toe into sport. It will mean not just stopping selling off school playing fields but buying them back, making physical activity a key part of the national curriculum as well as a focus of after school clubs. It will mean addressing activity inequalities among people of different genders, ages, races, and creeds and those with different abilities and household incomes. Only by taking a forensic approach to understanding all of these factors can we help the inactive to become more active.

None of this, of course, is to suggest that sport is a panacea. People will still suffer mental or physical damage who play avidly. But one thing we can be certain of is that it will help, both those who struggle who play and those who come to sport and exercise for the first time at a low point in their lives. Always effectively, but hopefully more noticeably than before, sport will also be preventing a series of issues that might, thanks to bats and balls and roads and trails, never see the light of day.